On the history and opportunities of hardware awareness

By Arya Tschand

Since the first line of code was written by Ada Lovelace in 1843 for Charles Babbage's "Analytical Engine," software has always shared an intimate and evolving relationship with the hardware it runs on. As computing evolved from abstract designs to general purpose processors to domain specific architectures, the art of programming became as much about knowing and exploiting the hardware as about expressing logic. At its essence, hardware-awareness is the understanding of how underlying hardware architectures influence software performance, efficiency, and capability, and the deliberate design of software to leverage those characteristics. While hardware-awareness has typically lived in the conversations between computer architects and the heuristics in compilers, it is now becoming essential knowledge for the much broader systems community.

In this blog post, I'll try my best to walk through the history of hardware-awareness across the computing stack and discuss opportunities to continue this trend in autonomous software and systems optimization with the help of Generative AI.

Background

The concept of hardware-software codesign is most commonly introduced in an undergraduate computer architecture course. In my freshman year CS250 course at Duke, Prof. Dan Sorin (who later became my undergrad advisor, mentor, and a significant reason why I chose to pursue a PhD) spent a semester walking us down the computing stack. From memory allocation in C to data movement in MIPS to integer arithmetic computation in RTL, we learned how to break down a workload into a series of steps that tells a processor what to execute. In the many software and systems courses I have taken since then, I have come to interpret hardware-software codesign as the process of designing hardware to support the most important software workloads and designing the software to best utilize the underlying hardware as it evolves. In practice, this has become a never ending cycle that continues to push the FLOPS of important workloads like machine learning inference.

For readers who are less familiar with how software and hardware communicate - most computer chips today have a specific ISA, or instruction set architecture, which is the interface that defines the specific language that software uses to tell the hardware what to do. Think of the ISA as the words of a spoken language, where "my name is Arya" in English and "mera nam Arya hai" in Hindi uses different syntax and sentence structure but semantically mean the same thing. Similarly, for the same semantic program running on different hardware, we must write the code differently to enable the specific hardware to effectively execute it. In practice, changing software is orders of magnitude easier and faster than changing hardware, so codesigning the software for the underlying hardware is a powerful tool.

Computer architects in industry and academia are obsessed with codesign. Before we even think about writing code, our conversations are filled with talks about profiling and relationships and exploration and tradeoffs. With the end of Moore's law and the need for specificity, it is impossible to design new hardware architectures without deeply understanding the important workloads today and taking bets on the important workloads tomorrow (and potentially 2 years from now). However, the rapid and often significant changes in new architectures have made it crucial for the software community to also have a deep understanding of the hardware. To offer an example, the Nvidia Blackwell GPU introduced the Nvidia Blackwell GPU introduced next-generation Transformer Engines, fifth-generation NVLink interconnects, and advanced memory hierarchies with unified HBM3e and LPDDR support. Some of these features require explicit use of new CUDA instructions (which compile down into the new SASS instructions that Nvidia adds to their ISA) or more abstract restructuring of the algorithm (to better exploit locality or package data).

My related work search for some future research I've been working on (that I'm excited to share soon!) took me down a rabbit hole about the history of hardware awareness, which has been explored all across the software side of hardware-software codesign. Fortunately for me, I can walk down the hallway at Harvard or shoot out emails to some of my amazing mentors who have been instrumental in creating our understanding of hardware-software codesign as we know it today. This blog is an accumulation of many of the things I've learned from them, which I hope is equally as insightful to the broader systems and software community as it has been for me!

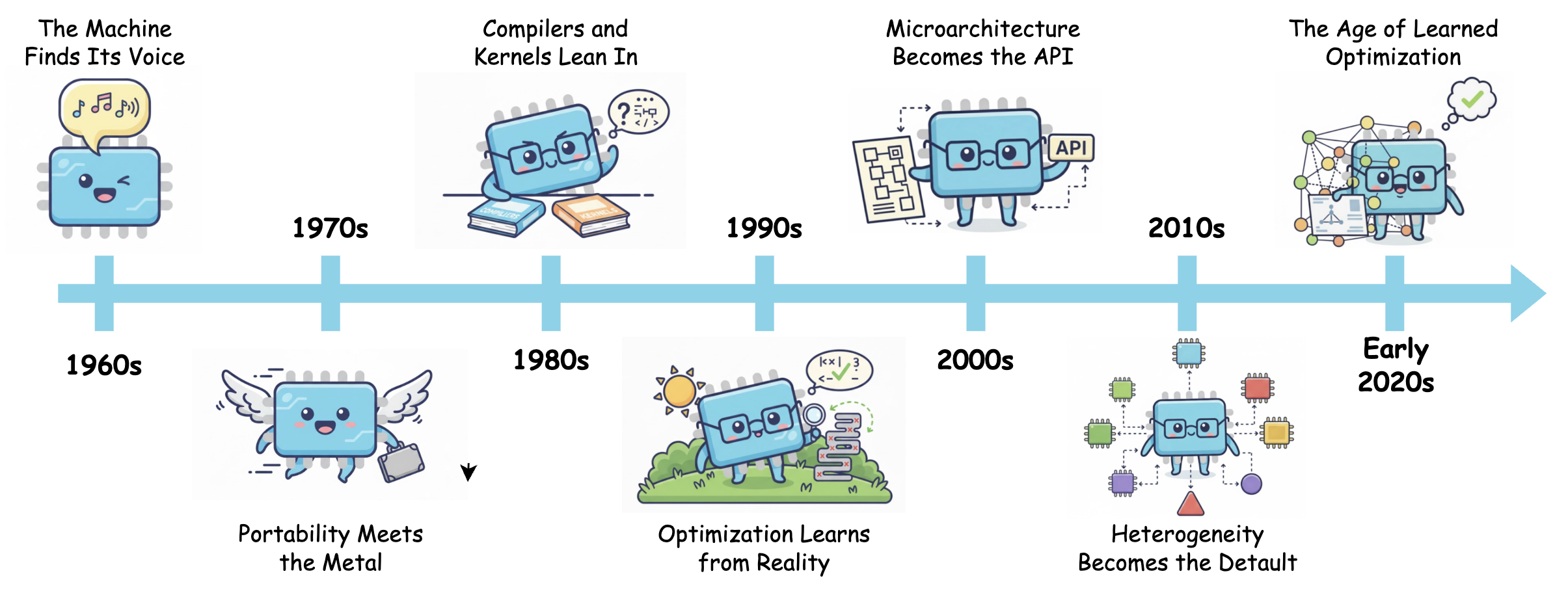

History

Many conversations with my PhD advisor Prof. Vijay Janapa Reddi start and end by relating our current ideas to seminal work in computer architecture, compilers, or programming languages, or machine learning. I've come to deeply appreciate the many different interpretations and approaches to using computer hardware to execute important workloads that these communities have offered. This progression of hardware awareness over the decades of computing innovation gives us insights into what information of the hardware matters to the software, and how past researchers have effectively taken advantage of these hardware features to make specific optimizations in the software. While hardware awareness in GenAI models will likely look different than it does in multicore compilers or OS scheduling, there are many parallels that are worth recognizing.

1960s — The Machine Finds Its Voice

The idea of hardware awareness truly begins in the 1960s, when computers first start to look the same from the programmer's point of view. IBM's System/360 in 1964 introduced a unified instruction set architecture across an entire family of machines. For the first time, portability became possible, but programmers still had to understand each model's personality and quirks. Around this time, Frances Allen at IBM was laying the foundations of compiler optimization. Her work gave compilers a way to reason about pipelines, control flow, and registers with structure rather than intuition.

Meanwhile, virtual memory was escaping the lab. The Manchester Atlas computer in 1962 and the later Multics project in 1969 treated memory as something that could be paged and cached dynamically, rather than as one long flat address space. These ideas taught software that memory had geography. Code could no longer ignore the shape of the machine beneath it.

1970s — Portability Meets the Metal

The 1970s carried that momentum forward. Software became portable, but programmers stayed close to the hardware. C in 1972 and UNIX matured together, giving developers a system language that was both portable and deeply expressive of the machine underneath. Programmers could move code between architectures, yet still reason about bits, pointers, and device interfaces.

At the same time, new architectures were teaching software to adapt. The Cray-1 in 1976 showed what was possible when loops were arranged to feed vector pipelines efficiently. Fortran compilers began to recognize patterns that could be transformed automatically for vector execution, and performance tuning became something a compiler could reason about instead of a human-only art. Toward the end of the decade, H. T. Kung introduced systolic arrays in 1979, where the algorithm itself is mapped directly to the flow of data on silicon. The idea that computation could be designed to match the hardware rather than the other way around began to take root.

1980s — Compilers and Kernels Lean In

By the 1980s, the partnership between hardware and software had deepened. Compilers were no longer simple translators. They became active participants in performance. Joseph Fisher's trace scheduling and Monica Lam's software pipelining showed how compilers could uncover instruction-level parallelism that processors were now capable of exploiting. Gregory Chaitin's register allocation through graph coloring turned limited registers into a constraint that the compiler could optimize globally rather than locally.

At the same time, hardware design itself was changing. The RISC movement simplified instruction sets and pipelines, putting more responsibility on compilers to deliver performance. Operating systems were also learning to surface more of the hardware to higher layers. CMU's Mach microkernel brought virtual memory and copy-on-write into view for user-level services. Numerical libraries, such as Level-2 BLAS, began to formalize cache blocking and data reuse, embedding memory hierarchy awareness into the very fabric of scientific computing.

1990s — Optimization Learns from Reality

The 1990s brought introspection. For the first time, compilers and systems began to study how programs actually behaved in the real world. Profile-guided optimization and path profiling helped reorder code to match instruction caches and branch predictors rather than idealized models. The polyhedral framework offered a rigorous mathematical foundation for loop transformations, making optimizations provably correct and tuned to locality.

Operating systems research also became bolder. The Exokernel project in 1995 exposed hardware resources like CPU time, memory, and storage directly to applications, allowing specialized libraries to implement their own policies. Empirical autotuning emerged at the same time. Projects like FFTW and ATLAS generated and timed thousands of code variants to discover what fit best with actual cache hierarchies and pipelines. OpenMP in 1997 made threading approachable for everyday developers. The reality of multicore was coming, and software was preparing to meet it.

2000s — Microarchitecture Becomes the API

The 2000s made the details of microarchitecture impossible to ignore. Power, cache size, and instruction width became things that software needed to care about directly. Tools like Wattch modeled power at design time, letting developers think about energy alongside performance. Dynamic binary instrumentation frameworks such as Intel Pin, DynamoRIO, and Valgrind gave programmers a window into real hardware behavior and created a feedback loop for optimization.

LLVM in 2004 introduced an intermediate representation flexible enough to describe calling conventions, vector widths, and cache hints in a single framework. Around the same time, mainstream compilers began auto-vectorizing loops for SSE and later AVX instruction sets. CUDA in 2007 and OpenCL in 2008 extended this control to GPUs, where memory hierarchies and thread organizations became explicit in code. Sparse kernels gained their own research attention through OSKI, and new operating systems like Barrelfish treated multicore and NUMA architectures as fundamental design constraints.

2010s — Heterogeneity Becomes the Default

The 2010s made hardware diversity the norm. Halide in 2012 separated an algorithm from its schedule, showing that performance could be tuned independently from correctness. NVIDIA's cuDNN in 2014 brought adaptive convolution libraries that changed behavior depending on tensor shapes and GPU models. Google's TPU paper in 2017 showed what full-stack hardware-software co-design could achieve when compilers were aware of systolic arrays from the start.

XLA and MLIR extended these principles, enabling compilers to target CPUs, GPUs, and custom accelerators through shared abstractions. Benchmarks like MLPerf established common hardware-aware performance goals that drove the entire field forward. Even everyday systems began to reveal more of their structure. Transparent Huge Pages and smarter memory allocators like jemalloc gave ordinary software the ability to control and adapt to the memory topology of the machine it was running on.

Early 2020s — The Age of Learned Optimization

In the early 2020s, hardware awareness began to evolve from manual tuning to machine learning. Autotuners like Ansor learned to optimize schedules without human templates, automatically adapting computation to caches, vector units, and tensor cores. Triton, which had started as a research prototype, became a widely used GPU language that gave developers the tools to express shared-memory tiling, coalesced memory access, and warp-synchronous execution naturally.

Attention mechanisms themselves became examples of hardware-aware redesign. FlashAttention in 2022 reformulated the transformer's attention step to minimize data movement across high-bandwidth memory, showing how algorithmic ideas could emerge directly from hardware constraints. Production systems began to incorporate this mindset. CUDA Graphs and asynchronous memory copies in NVIDIA's Ampere GPUs made low-level optimization patterns part of mainstream deployment. Full-model compilers such as Meta's AITemplate started producing fused binaries tailored for each GPU family, while SYCL 2020 unified heterogeneous programming in modern C++.

Each of these developments pushes us closer to a new frontier, one where software not only understands the hardware it runs on but can learn from it in real time. Hardware awareness is no longer a rare skill for specialists; it is becoming the foundation for how intelligent systems will design and optimize themselves in the years ahead.

Opportunities

GenAI for Systems Optimizations

As readers are likely familiar with, Generative AI has fundamentally enabled us to solve problems that were not possible before. We can now take advantage of the abilities to draw far reaching relationships (with attention), train on massive datasets (with parallel transformers + lots of GPUs) generate new and continuous outputs (technically discrete in the tokenization space, but this tokenization space is so big that it is almost continuous). This enables us to solve difficult and continuous problems that have never been solved before. For example, computer vision researchers spent over a decade refining convolutional and recurrent architectures to capture long-range spatial dependencies, but these approaches always hit limits on context and scalability. Transformers solved this almost overnight by using self-attention to model global relationships in parallel, letting the model see the entire image at once rather than through local filters.

GenAI has already led to incredible progress in fields like biology, law, and banking, and even at the top (software engineering) and bottom (physical chip design) of the computing stack. However, for a variety of reasons, we are still figuring out how to best use GenAI to make impactful optimizations in the middle of the computing stack (computer architecture and hardware-software codesign). Even if we start at the foundation, our lab's work with QuArch showed that frontier LLMs struggle in reasoning about certain computer architecture knowledge. While there is plenty of reason to believe that future models will continue to gain more knowledge and reasoning capabilities for effective hardware-software codesign, this raises the question "Does the knowledge even exist in writing or is it intrinsic?" To learn more about this, I encourage you to check out this blog post we wrote up for our Harvard CS249 course.

Performance Engineering

This weak foundation propagates to downstream applications in software design. LLMs are nearly superhuman at software engineering and algorithm design, but struggle with performance engineering. Let's compare these seemingly similar problems a bit more.

Software engineering is trying to write code that is functional and does what the user wants. This is inherently hardware-agnostic because compilers guarantee that the functionality doesn't change based on the hardware you are running it on. Cursor + GPT-5 is far better and faster at software engineering than I ever will be!

Algorithm design is restructuring the workload to be asymptotically faster, which deals with performance in a computational complexity lens but is still hardware-agnostic. OpenAI and DeepMind both showed that their frontier LLMs can achieve IOI gold medals.

In contrast, performance engineering is changing the code implementation to be performant for the underlying hardware. While many core principles generalize, the exact implementations for performance engineering can change significantly based on the hardware. Also, using profiling tools to isolate the performance bottlenecks to optimize for becomes a challenge in itself for large systems. Our lab's recent work SWEfficiency showed that even with profiling tool use and an inference budget in the thousands of dollars, frontier LLMs struggle (<15%) to implement performance improving edits in real-world codebases.

GPU kernel optimization is an interesting case study on the missing pieces in autonomous performance engineering. Compared to CPUs, GPU architectures change a lot more between generations and expose a lot of these changes to the programmer to exploit. Exploiting these hardware changes in the code is so important that performance engineers who write great CUDA code spend most of their time thinking about ways to best utilize the hardware. In practice, this is slow and very difficult, which explains the many month process to port code from an old GPU architecture like Nvidia's Hopper to a new one like Nvidia's Blackwell. This is so difficult, that we still haven't finished porting all our code for Blackwell despite its release over 1 year ago!

Anyone (including myself) that has written CUDA code has probably tried to ask an LLM to do it for them. Our friends and collaborators at Stanford had a great idea just about a year ago to benchmark how good LLMs are at writing performant GPU kernels. Their work with KernelBench has sparked an amazing body of work in autonomous kernel optimization, but a quick glance at the LLM generated kernels shows us that they struggle to use even the most important GPU functional units like the tensorcore and thread memory accelerator (TMA). Through some of our new work, we observe a significant gap between LLMs ability to understand knowledge of GPU architectures (they are really good at this) and actually implement these architecture-specific features in code optimizations (still a work in progress).

My recent paper SwizzlePerf (to appear as a Spotlight at the NeurIPS 2025 ML for Systems workshop) showed that with the right ingredients for hardware awareness like architecture documentation, few shot examples, and scheduling information, we can begin to make optimizations that utilize architecture-specific features like AMD MI300's disaggregated memory hierarchy. Stay tuned for our announcements of some new work that makes this more generalizable soon!

Scheduling and Beyond

Scheduling is another future target for hardware-aware GenAI optimization. A model that can see NUMA layout, HBM versus DDR tiers, NVLink or PCIe links, MIG partitions, and live power and thermal headroom can propose placements, prefetch windows, and concurrency levels that fit the machine in that moment. Instead of one fixed heuristic, we get a learned policy that tunes throughput and tail latency under fairness and isolation, using counters and telemetry as feedback. In practice this means co-designing CPU pinning and GPU affinity, staging tensors to the right memory tier, choosing stream priorities and CUDA Graph usage, and adjusting DVFS or power caps only when the SLO requires it.

If scheduling reacts to the live machine at runtime, the compiler decides what executable the runtime inherits. Codesigning the coding agents with the compilers turns that decision into a feedback loop where an agent edits source or IR, tunes pass order and parameters, and learns a cost model tied to the ISA, caches, and interconnect. The workflow is simple to state: profile a workload, generate candidate schedules and layouts, compile and run, collect counters and power, update the policy, then lock in configurations that consistently win. The compiler keeps legality and portability, while guardrails like tests, differential checking, and memory-model validation preserve correctness as performance improves.

To make that loop tractable for real applications, the programming model needs to expose optimization decisions cleanly. Domain-specific languages that separate algorithms from schedules let an agent search tile shapes, fusion patterns, data layouts, and asynchronous copy strategies that match matrix units, SRAM sizes, and link bandwidth. Hardware descriptions can become richer and more standardized, so a single schedule adapts across devices with small edits rather than rewrites. The toolchain can carry checks for safety, emit counterexamples when a transform is unsafe, compile to multiple back ends in one build, and continue to refine schedules online using telemetry.

Thanks for reading - feel free to reach out to me via email (aryatschand@g.harvard.edu) or X (@aryatschand) with any questions, feedback, or suggested changes/fixes!

Acknowledgements

My professors and mentors at Duke (Dan Sorin, Lisa Wu Wills, John Board) and Harvard (Vijay Janapa Reddi, David Brooks, HT Kung) for teaching me everything I know about our rich history in computer systems and showing how we can apply it to continue making breakthroughs.